The Stars of St. John’s Church Lunenburg

(Original version published in the 2005 Vernal Equinox issue of Cassiopeia, http://www.casca.ca/ecass/issues/2005-me/)

St. John’s Anglican Church in Lunenburg, which dates from 1754, is the second oldest protestant church in Canada. The original church design was modified a number of times since its original construction, the most recent occurring in 1870-71 when its present Gothic Victorian interior was constructed. The Church is a well known landmark in Nova Scotia, and appears as a backdrop in the 1998 Hollywood Pictures movie Simon Birch. The Church was designated as a National Historic Site in October 1998. Lunenburg itself is a World Heritage Site.

Left: St. John’s Church, Lunenburg, prior to the fire of October 31, 2001. Right: The chancel area after the fire. Images courtesy of Parks Canada and St. John’s .

Disaster struck on the evening of October 31, 2001, when the Church was destroyed by a fire apparently set as a Halloween prank. With remarkable fortitude the Church congregation voted to restore St. John’s to its original condition prior to the fire, and reconstruction at the site began almost immediately. Much of the early effort involved reconstructing the Church exterior, but by 2004 it was time to contract out work on the interior. The company selected to restore the original Gothic artwork was Era Studio in Lunenburg, operated by Julie-Jayne (JJ) Coolen and her mother Margaret Coolen.

In late May 2004 I began a correspondence with Margaret Coolen, who had contacted Hugh Couchman, Secretary of CASCA, for assistance in identifying the pattern of stars that had originally graced the ceiling in the chancel portion of the Church. Although there had been many photographs of the Church interior taken prior to the fire, Margaret did not have sufficient coverage of the star patterns in order to reproduce them as they had originally appeared. She also noticed that the distribution of visible stars was not truly random, and sought the assistance of someone familiar with the constellation patterns of the night sky.

Margaret and JJ visited my office in late June to loan me photographic enlargements of portions of the chancel ceiling, along with a CD of additional images in the collection of Parks Canada and the Church. The star patterns were apparently referred to locally as a “mariner’s sky,” although Margaret wondered if they might instead relate to the first Advent. I had previously checked the geographical orientation of the Church in case the stars represented a scene from the site itself. I had visited the Church many times prior to the fire, but had only vague recollections of the chancel ceiling, and was unaware of any significance to the stars painted there.

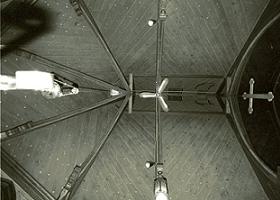

The images of the ceiling immediately illustrated the problem faced by Margaret and JJ. Because of the nature of the stars, which are gilded, and the poor lighting of the ceiling, only photographs of the eastern ceiling panel display the full complement of stars placed there, and some are obscured by a lantern chain. In images covering adjacent panels, many stars are not sufficiently illuminated to show up on photographs. The chancel ceiling itself is similar to a dormer roof. It contains two panels on each of the north and south faces, one rectangular and the other quadrilateral, and three eastern panels of triangular shape, all seven panels forming a rounded eastern roof to the chancel. The ceiling dates to the 1870-71 renovations, but the stars are not visible in images of the church interior taken around 1900-10. Parish records have not revealed further details about their origin.

Left and Right: The chancel stars as they originally appeared. Images courtesy of Parks Canada and St. John’s Church.

Like Margaret and JJ, I was initially puzzled by the star patterns. The distribution is somewhat random, but includes a non-random component suggestive of constellations. The star images differ in size in a manner suggesting their actual brightness distribution in the night sky. Despite my years of experience operating the planetarium at Laurentian University, I was just as puzzled as my visitors by what the star patterns might represent.

After about five or ten minutes of that first meeting I was able to identify a specific clump of stars on the eastern panel that seemed familiar. Further checking revealed the pattern to be the constellation Perseus, although with a few stars missing and a few extras included. I was later able to trace out most of the constellation from the visible stars, although it helped matters to invert the original black and white images to make the panel images more like observational finder charts. On my graphic printouts I sketched the outline pattern of the constellation as it appears in standard star charts.

Perusal of adjacent fields confirmed the identification of Perseus on the eastern panel. With a bit of artistic license I was able to identify many of the constellations adjoining Perseus: Aries, Camelopardalis, Lynx, Pisces, etc. The chancel ceiling appeared to represent a standard view of the night sky, in fact as it would appear through the ceiling rafters, complete with the loss of thirty degrees of sky above the horizon to the chancel walls and many overhead stars to the framework of rafters holding up the ceiling panels. It bothered me that many of the more spectacular constellations, such as Orion, Ursa Major, and Taurus, were not present because of the 30° horizon cutoff, and that Cassiopeia was missing because its bright stars lay in the direction of the rafters. The original star scene was rather bland for a church ceiling.

Left: A negative view of one of the better images of the eastern panel, showing the original star scene depicted there. Image courtesy of Parks Canada and St. John’s. Center: Reid Coolen helps his daughter JJ lay out the new star pattern on the chancel ceiling. Right: Julie-Jayne Coolen laying out the new pattern for the stars. Images courtesy of Ed Jordan.

The major motivation for Margaret’s contact with an astronomer was the need to produce a new layout for the ceiling stars that would replicate, as closely as possible, the original star scene. I therefore spent some time after my meeting with Margaret and JJ establishing the time and geographical location of the scene painted on the ceiling panels. The location of Perseus in the middle of the eastern panel was a bit of a mystery. In today’s skies the constellation cannot appear above the eastern horizon as it did in the eastern panel because it is located only 40° from the north celestial pole. Diurnal motion always carries Perseus on a path that falls to the north of due east. My attempts to reproduce the orientation of the constellation using desktop planetarium software (Earth Centered Universe, which is distributed to Department members by its creator, Department technician and observatory director Dave Lane) failed to match the appearance of the stars on the chancel ceiling. Even a reorientation of the ceiling panels did not produce a match to the star pattern of the ceiling.

Following Margaret’s suggestion of the first Advent, I set the planetarium software to reproduce the scene from two thousand years ago, using sunset of the first Christmas, established by setting the Sun on the western horizon, as a means of initiating a further search. Because of my background in writing scripts for planetarium Christmas Star productions, I initially set the scene for Bethlehem. Perseus was 10° further from the north celestial pole in that era, so it did swing over the eastern horizon each day two thousand years ago. To my surprise, the sky for sunset of the first Christmas placed Perseus much as it appeared in the ceiling star scene, but the orientation was skewed. A readjustment to the latitude of Lunenburg was all that was needed to bring the scene into close agreement with the star pattern facing me from the “finder chart” I had made for the eastern ceiling panel.

I immediately forwarded the news to Margaret and JJ about the apparent origin of the star pattern as a replication of the scene at sunset of the first Christmas, but it worried me that the stars would not actually be visible at that time. Margaret’s husband Reid, a retired church cleric, pointed out the likely significance of sunset, which marks the end of one day and the beginning of the next in Jewish tradition. The star scene replicated on the chancel ceiling of St. John’s was apparently chosen to mark the beginning of the first Christmas as seen from Lunenburg. Subsequent discussions with local historians and with Randall Brooks, chair of CASCA’s Heritage Committee, confirmed that deduction.

The nature of the discovery raised many additional questions. Was the meaning of the original star scene of the chancel ceiling not known to parishioners? Who had created the design for the star patterns displayed on the ceiling? And how was it produced? Randall Brooks helped answer some of those questions. Star patterns apparently decorate the domes of many churches, including several in Europe, eastern U.S., and eastern Canada. Churches are often oriented such that their chancels lie on the eastern end, so scenes replicating the first Christmas include the stars of Perseus in prominent view. Previously existing layouts for the pattern may have been used at St. John’s, or the scene may have been created locally by someone possessing an astronomical background. Somehow the meaning of the starry ceiling had been lost over the years.

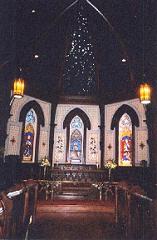

Left: The restored chancel ceiling, centered on the eastern panel. Right: Julie-Jayne Coolen and I admire the new ceiling design. Images courtesy of Margaret Coolen.

It took about a week early in September for me to generate a new pattern for JJ and Margaret to follow in replicating the original star scene. A brief evening visit to Lunenburg established that the chancel end of the Church actually faces 5° south of east rather than due east, so I laid out the new pattern based on the actual Church orientation, using a bit of artistic license to make the star scene match the original layout as closely as possible. The original ceiling display had apparently contained 700 stars (yes, someone counted them!), so I generated plans that included faint enough stars to bring the resulting total to that number. JJ and Margaret Coolen spent the next two and a half weeks plotting the new star pattern on the newly painted wooden ceiling, then gilding stars of different sizes to the planks using a magnitude reference scheme I included in the plans. The newly renovated chancel ceiling was completed a few days prior to a press conference held at St. John’s on October 7 to announce partial funding for the renovations from American Express.

Whatever feelings I may have felt on my initial reply to Margaret Coolen’s inquiry about the Church stars have been long forgotten in the wake of the overwhelming media response to the story. The finished chancel ceiling is a spectacular sight thanks to the meticulous work of JJ Coolen, and will be a drawing card for Church visitors in years to come. The original star scene depicted on the ceiling was almost obscured by the passing of the years, the fading of the original colour scheme, and the weathering of the ceiling panels. The newly renovated ceiling with its rich deep blue background and gilded golden stars is a striking artistic portrayal of the sunset star scene that would have been visible through the Church rafters on the traditional date of the first Christmas. Star gazers will have no trouble recognizing the familiar constellations adjacent to Perseus in the night sky.

It has been a tremendous experience to have played a role in the recovery of a lost portion of St. John’s Church heritage.

A video from the Discovery Channel airing of the story in October 2004 can be found here Discovery Channel Video. The program won the L’Oreal Excellence in Science Journalism award for its producer.

Scenes from the restored St. John’s Church, December 2005. Left: The Church chancel, with the renovated eastern ceiling panel above. Center: The restored Fisherman’s Window at St. John’. Right: The restored Church exterior now is identical to its original appearance.